- AI-Native Training

- SAFe Training

- Choose a Course

- Public Training Schedule

- SAFe Certifications

- Leading SAFe

- SAFe Scrum Master

- SAFe Product Owner/Product Manager

- SAFe Lean Portfolio Management

- SAFe Release Train Engineer

- Implementing SAFe

- Advanced SAFe® Practice Consultant

- Advanced Scrum Master

- SAFe for Architects

- SAFe for Hardware

- SAFe for Teams

- Agile Product Management

- SAFe DevOps

- SAFe Agile Software Engineering

- Leading SAFe for Government

- SAFe Micro-credentials

- Agile HR Training

Release Train Engineer - Batman or the Wonder Twins?

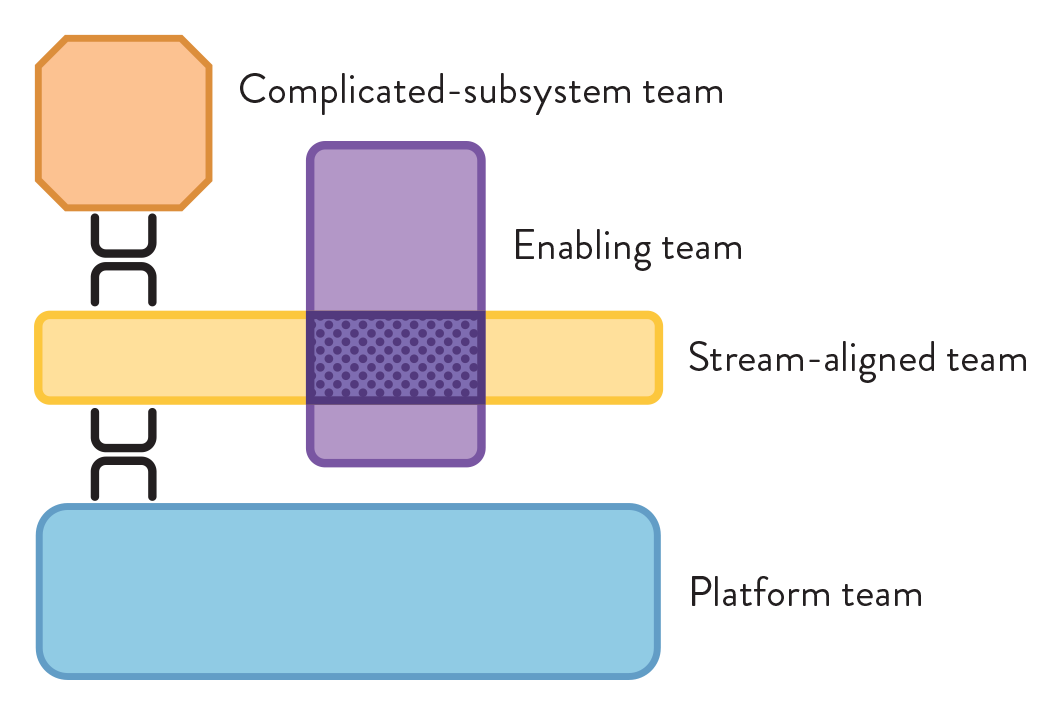

A couple of months back I wrote about launching my first Agile Release Train and some of our specific challenges with creating the right organisational structure. In particular I pointed out that : “For us the Release Train Engineer (RTE) role as articulated in SAFe has never really emerged. “ Instead, the responsibilities spelt out in the SAFe Big Picture as belonging to the RTE have in our case ended up being split across the leads of the three service teams - Pipeline Services, Development Services and Deployment Services.

Initially we had envisaged the Development Services Manager would be the RTE, however it quickly became apparent that it would take a superhuman effort for one individual to take on all the responsibilities of an RTE, especially when your Agile Release Train is swimming against the tide in an organisation that has yet to embrace Lean|Agile mindsets. Enter the role of the Pipeline Services lead, Megan Anderson and her team. These superheroes stand shoulder to shoulder defending the front line every day. The pressure from the broader organisation to compromise on our values is constant and unrelenting. But they stand firm and protect the development teams.

Every day it is that same conversation:

“No, we will not pressure the development team to reduce the estimate. You need to trust the team. If you do not have enough funding consider de-prioritsing some features.”

“No, the team will not work every weekend between now and Christmas. We only work at a sustainable pace. If your project is critical let’s collaborate with other stakeholders to have your features prioritised appropriately.”

“No, we will not throw more “resources” at the problem. Nine women cannot make a baby in one month!”

“No, you cannot “buy” teams. If your Epic is important to the company you will need to have it prioritised accordingly.”

“Yes, the plan has changed. We have learnt more about your needs.”

“Yes, the plan has changed. We have been unable to get time with the business feature owner. If this is important to you, you will make the right people available to support the team.”

(Just writing this list has reinforced for me again the importance of training everyone - including your business stakeholders and the other technology groups you work with.)

If you are fighting on the front line every day, it is difficult to also find the time and energy to be the facilitator of train ceremonies and the champion of continuous improvement. I was trading notes on this conundrum recently with a colleague and we reached the following conclusion:

In large enterprises where agile is starting out and the people on your first agile release trains are in the minority and traditional mindsets are the norm, splitting the RTE role into two may well be a better place to start for the sanity of the RTE and those who are dependent on him or her.

In other words launching an Agile Release Train while standing in a waterfall presents two key challenges: (1) how to grow a high performing team of teams and (2) how to protect the train and/or grow the enterprise. If these two challenges fall to just one person, even a superhero is going to need to compromise the attention given to one or the other. As Dean Leffingwell says, “nothing beats an agile team”. When the teams are new to agile, the organisation needs to make a serious investment in nurturing those teams, to become unbeatable. In an Agile Release Train of 50 - 125 people this is a big job. On the other hand, in an organisation new to agile, the first agile release train runs the risk of being run off the tracks by the traditional mindsets of the governing bodies and dependent technology teams.

Of course like every compromise this scenario creates its own challenge as each side of the two headed RTE struggles to recognise the value of the other. Inevitably while Megan’s team struggled heroically to buffer the train from organisational pressures, there was always leakage. Their success in some ways contributed to the tension, as the development teams were largely unaware of just how much they were being shielded. While the development teams were striving to empathise with their customers, their ability to build empathy for what many still perceived as a “project management layer” was often neglected. In creating a responsibility split of “grow the teams” and “protect the teams”, it will inevitably create tension between the two mandates when it comes to separating the crisis of today from the promise of tomorrow.

With my overarching context, my mission was to assist my leadership team in navigating this tension. I often struggled, as I could so easily see their combined power. Recently, I found some valuable insights with respect to the cause of some of the tension while reading Adam Grant’s Give and Take. In a chapter dedicated to exploring “Collaboration and the Dynamics of Giving and Taking Credit”, he introduces the concept of responsibility bias from the work of Canadian psychologists Michael Ross and Fiore Sicoly. Responsibility bias occurs when we exaggerate our own contribution relative to others. While in some instances this can be ego driven, it is also a natural byproduct of information discrepancy. “We have more access to information about our own contribution than the contributions of others. We see all of our own efforts, but we only witness a subset of our partners’ efforts. When we think about who deserves the credit, we have more knowledge of our own contributions.”

Occasionally I facilitated retrospectives and empathy mapping workshops amongst the leadership team, mainly when tensions had reached “boiling point”. In looking back I suspect I should have looked at a more continuous cadence. That said, they have started to solve the problem for themselves in recent months. Recently Megan commented on the insights that have emerged from encouraging her Project Portfolio Managers to spend time sitting out with the teams. Having the development teams absorb osmotically the number of times the Pipeline team says “no” to the machine has been very powerful.

In closing, I still think we made the right call in splitting the RTE role and I would do it again. However next time I will be conscious that “responsibility bias is a major source of failed collaborations” and put the right rituals in place to help these highly effective independent superheroes become an even more effective pair of Wonder Twins.